It is generally a bad idea to get in the government’s crosshairs. After all, the Justice Department has powerful tools at its disposal — among them, the vast machinery of federal law enforcement and the ability to gather information that literally no one else can legally obtain. These are just some of the reasons why the government has a roughly 95 percent conviction rate in criminal cases.

But the Justice Department’s most potent asset is the credibility of its lawyers.

Judges and juries alike tend to trust DOJ lawyers out of the gate — even ones they have never met before — by virtue of their positions and their obligation to uphold the Constitution and advance the public interest. Many federal judges were once Justice Department lawyers themselves. All day every day, in federal courthouses across the country, the Justice Department benefits from a general presumption of good faith when a DOJ lawyer walks into a courtroom because people assume that they are both honest and well-intentioned.

That may be changing.

In the few first months of President Donald Trump’s second term, Justice Department lawyers have come under fire from judges across the country in some of the most high-profile cases that have emerged since his inauguration. The comments have been unusually sharp — at times directly questioning the honesty of the government’s lawyers and the accuracy of their factual claims — and taken together, they suggest that the administration’s officials are squandering the department’s credibility just when they need it most.

The accumulating record under Attorney General Pam Bondi and other new political appointees has become impossible to ignore and could pose a real threat to the success of the administration’s most aggressive legal forays.

The frustration may even have reached the Supreme Court.

In mid-April, the Supreme Court issued a remarkable, middle-of-the-night rebuke to the Justice Department when the court stepped in to order the government to stop deporting Venezuelan immigrants detained under the purported authority of the Alien Enemies Act. The order came after lawyers for the detainees said that a second wave were about to be flown out of the country. Only two of the six Republican appointees, Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito, dissented.

Perhaps not coincidentally, the ruling came shortly after the Supreme Court directed the government in early April to “facilitate” the return of Kilmar Abrego Garcia from El Salvador. Since then, the Justice Department has argued to the lower courts that the Supreme Court’s instruction to “facilitate” Abrego Garcia’s release meant — as a well-regarded conservative appellate judge summed up the government’s position — that they could “do essentially nothing.”

Nearly a month later, Abrego Garcia is still in a Salvadoran prison.

Whether the Supreme Court grows more skeptical toward the Trump administration’s credibility — and its broader agenda — may become clear in the coming weeks.

The Trump DOJ’s credibility problems first emerged this spring during highly charged litigation across the country — often in cases in which political appointees or newly positioned line attorneys were representing the government.

In March alone, at least four different judges laid into Justice Department lawyers.

A judge in California concluded that the administration had engaged in a “sham” strategy to fire probationary federal employees by falsely claiming that the dismissals were the result of poor performance. “I tend to doubt that you’re telling me the truth,” the judge told a Justice Department lawyer defending the government.

The same day, another judge handling a challenge to the firings in a different court was equally dismissive of the government’s purported rationale: “On the record before the Court,” the judge wrote, “this isn’t true.”

Later that month, the judge overseeing the challenge to the administration’s ban on transgender people in the military concluded that the government’s arguments were “littered with animus and pretext.” “You’re saying one thing in public. You’re saying a different thing in court,” she told government lawyers during a hearing. As my colleagues noted recently, that has been a recurring issue for the Trump administration.

And after the administration tried to remove the presiding judge overseeing the law firm Perkins Coie’s challenge to an executive order targeting the firm, the judge chastised the government for relying on “speculation, innuendo, and basic legal disagreements.” She also criticized the government for using rhetoric that sounded more like “a talking point from a member of Congress rather than a legal brief from the United States Department of Justice” — a now-common feature of briefs filed by the Justice Department in politically charged cases.

Things got worse in April.

The judge who eventually dismissed the criminal case against New York City Mayor Eric Adams took the government to task for making arguments that were “unsupported by any objective evidence,” “pretextual” and “unsubstantiated.”

Two weeks later, the judge presiding over the initial challenge to the administration’s use of the Alien Enemies Act concluded that there was probable cause to find that the government had engaged in criminal contempt of the court’s order requiring the first planes to return to the U.S. He accused the Justice Department of attempting to “muddy the waters” in the inquiry.

The following week, in the Abrego Garcia case, U.S. District Judge Paula Xinis accused the government of attempting to “obstruct” discovery in the case and providing “vague” and “evasive” answers that were tantamount to “a willful and bad faith refusal to comply.” (Years ago as a prosecutor, I appeared before Xinis in court. She was both a consummate professional and, so far as I could tell, not inclined to make serious, baseless accusations against government lawyers.)

Two days later, in a challenge to Trump’s executive order purporting to change how elections are administered throughout the country, a judge faulted the government for a “contradiction between [the government’s] factual representations and the facts on the ground.”

One day after that, in a case in Texas challenging the detention of two people detained under the AEA, a judge found that the government’s claims were “replete with conclusions, declarations, and accusations, completely and wholly unsubstantiated by anything meaningful in the record.”

To close out the month, a different judge found that the administration’s rationale for revoking federal collective bargaining rights from federal employees — supposedly for national security reasons — “was mere pretext for retaliation and for accomplishing unrelated policy objectives.”

Alongside the judges, the administration’s approach has frustrated the government’s adversaries in court.

“Litigating against this administration is requiring that lawyers expend additional resources to raise compliance issues with the courts, after the courts issue orders providing plaintiffs relief, in order to make sure that court orders are actually followed,” said Skye Perryman, the president & CEO of Democracy Forward, a legal advocacy organization that has frequently tangled with the administration.

The examples above all involve questions about whether Justice Department lawyers attempted to mislead the presiding judges. A different but closely related issue concerns the Trump Justice Department’s evasiveness in court — which was on full display last week in the AEA litigation.

Justice Department lawyers are opposing a renewed effort to litigate the legality of the AEA deportations in the District of Columbia before U.S. District Judge James Boasberg, and one of their principal arguments is that the government has no custody or control over the detainees in El Salvador and therefore no ability to seek their return. That’s despite the Trump administration having paid the Salvadoran government $6 million to become the government’s de facto prison contractor.

There is also the not-so-small matter of Trump’s admission — just days ago — that he “could” have Abrego Garcia returned to the U.S. if he wanted. All he has to do, Trump acknowledged, is pick up the phone.

Before Trump, a concession like that in the context of high-profile, ongoing Justice Department litigation would have been a disaster for the government, which would have scrambled to explain how the president’s comments did not actually undercut their case.

But during Trump’s first term, the Republican appointees on the Supreme Court granted Trump considerable leeway in this area — most notably, when they upheld Trump’s so-called travel ban in 2018 and ignored Trump’s long record of anti-Muslim statements as the rationale for imposing restrictions on an array of Muslim-majority countries.

This accommodation has not been lost on Trump’s current lawyers at the Justice Department. They pointed directly to the Supreme Court’s ruling in the travel ban case when they told judge Boasberg in their brief last week that “public statements by officials have not been credited as evidence of the purpose behind an executive policy.” “Even statements by the President have been held not to establish the purpose behind a particular executive policy,” they wrote.

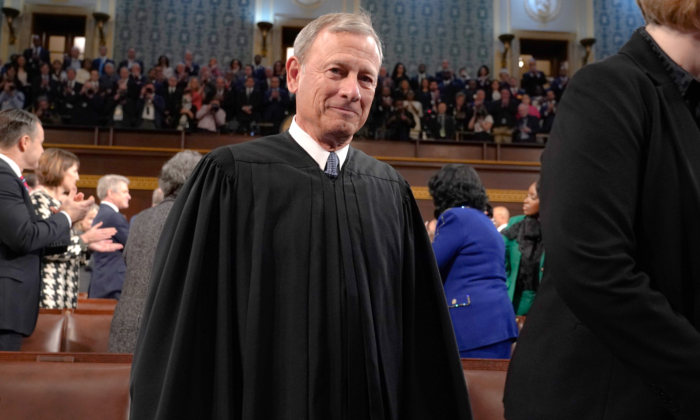

There appeared to be some limits to this indulgence during the first term, at least on the part of Chief Justice John Roberts.

In 2019, Roberts joined with the four Democratic appointees on the court at the time to question the veracity of the administration’s claims in support of its effort to add a citizenship question to the 2020 census. The government told the courts that it was adding the question to help enforce anti-discrimination provisions in the 1965 Voting Rights Act, but after reviewing records from within the Commerce Department, Roberts concluded that the rationale appeared to have been “contrived.”

“We are presented, in other words,” Roberts wrote, “with an explanation for agency action that is incongruent with what the record reveals about the agency’s priorities and decisionmaking process.”

This was a very diplomatic way of saying that the administration and the government’s lawyers had tried to mislead the court.

Of note: Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was still on the court at the time. The composition of the court shifted further in favor of Trump after her passing, when the administration named Justice Amy Coney Barrett to the bench to replace her. Barrett’s handling of similar issues — and her willingness to question the government’s claims — could prove decisive in key cases in the months and years to come.

There is reason to question whether the other Republican appointees will be as skeptical of the administration. Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh all declined to sign on to the portion of Roberts’ opinion in the census case questioning the government’s honesty.

All six of the conservative justices — Roberts and Barrett included — also ruled in favor of a state football coach who had been suspended after holding prayers on field following games. They did so despite a sharp dissent from Justice Sonia Sotomayor, complete with photos, that argued that the coach — and the conservative justices — had seriously “misconstrue[d] the facts” about what had actually happened.

We may soon get a test of the Supreme Court’s current willingness to indulge the administration and its lawyers.

Next week, the Supreme Court will hold the most consequential oral argument of the year so far — over whether lower court judges can block administration policies through so-called nationwide injunctions. The underlying vehicle for the argument is Trump’s executive order to end birthright citizenship — the merits of which are not supposed to be at issue but, as a practical matter, are impossible to ignore.

The administration’s effort to end birthright citizenship has been rejected as unconstitutional by every court that has considered it, and there is near-unanimous agreement on this point among credible scholars and lawyers.

Despite this, the Trump administration is asking the Supreme Court to limit the injunctions to only those people who are parties to the pending birthright citizenship cases. The government does not spell out the full implications of its position, but that means any injunction would only cover the seven expectant parents who are parties to the cases.

If the court sides with the Trump administration here, it will effectively give the government permission to end birthright citizenship throughout the rest of the country unless and until the Supreme Court rules that the effort is unconstitutional on the merits.

In the meantime, countless children — the children of both undocumented immigrants and temporarily legal immigrants — could be born stateless and deported.

The Justice Department has sought to downplay the fallout from a ruling in their favor, arguing that the results would not be as calamitous as the challengers have claimed — that the courts would be well-equipped to handle the ensuing litigation without chaos throughout the nation or widespread, irreparable harm to the people affected in the meantime.

To accept the Justice Department’s claims, however, you have to trust them — or at least pretend to trust them — despite the steady drumbeat of lower court judges who have effectively described numerous DOJ lawyers as dishonest, unreliable or both.

We may get our first real sign next week of whether these credibility concerns have reached any of the Supreme Court’s Republican appointees — who are now entering a period in which they will have to directly and substantively engage with the Trump’s administration’s unprecedented effort to expand the powers of the presidency, and who now hold the fate of much of Trump’s second-term agenda in their hands.

.png)

English (US)

English (US)