CARACAS, Venezuela — I woke up sometime after 2:30 a.m. Standing in front of me was my brother-in-law — who had shaken me awake as I dozed on a pull-out sofa. It was dark. Through the windows I could make out the beach: rows of huts with dried palm-leaf roofs, part of the beach club where we were staying, a members-only compound on the coast, more than an hour from Caracas, with apartments and houses mostly owned by Caraqueños who retreat there on weekends and holidays.

“Check your phone,” he said. “I have many missed calls from my dad. And a message saying they’re bombing La Carlota and Fuerte Tiuna.” He was referring to the military airport and the sprawling base embedded in the Caracas metropolitan area.

“I lost signal,” he added. “The Wi-Fi’s down too.”

I bolted upright and grabbed my phone. No signal. We stared at each other — confused, frozen, in shock.

“Is it a coup?” I asked.

And then it clicked: Maybe this isn’t a coup.

Maybe it’s the Americans.

My sister woke up soon after, alarmed by our voices. Once we explained what was going on, she handed us her phone — an overseas e-SIM. It worked. We opened social media and saw what had seemed impossible. Explosions near the Caribbean coast by a neighboring beach club. Orange fireballs lighting up the hills of Caracas and a line of American helicopters cutting across the city’s sky. Car caravans fleeing Fuerte Tiuna. Campers up on El Ávila — the massive mountain that looms over Caracas — filming a panoramic view of the metropolis: endless twinkling lights, punctuated by sporadic blasts of firepower here and there.

Just hours earlier, under a bright full moon, the beach had been packed. Families loudly chatting, young people playing beach volleyball, children running around and people arguing over whether the Americans would finally do something after five months of escalation. The clatter and chaos of chairs, whisky bottles and rum. Now, it looked as if war had descended upon us.

Then the Wi-Fi came back. I grabbed my phone and, like a storm breaking, hundreds of messages flooded in at once. Private messages. Group chats. “Did you hear it?,” many asked. “Are you guys okay?,” others wanted to know. There were dozens of videos. It felt as if all of Caracas had jumped awake at the same time, shaken by the blast.

“This is the worst thing I’ve ever heard,” one friend wrote. “Looks like they hit El Volcán,” another said, referring to the green-and-yellow hills to the southeast, where we usually go hiking on weekends, crowned by communications towers — including one operated by my phone carrier, which explains why I lost signal.

My legs started shaking as I watched the videos. I called my mom in Caracas. “I heard the explosion,” she said, rather unfazed. “I’m okay.” By then, the bombing had already stopped. But many in the city — anxious, alert — kept listening to the rumble of helicopters hidden in the darkness of the night sky.

The three of us sat together, endlessly scrolling social media — rumors, leaks, actual news, anonymous informants — trying to piece together what had even happened. Then my sister got a call: It was the mother of one of my nephews’ schoolmates, also staying at the club. “Go to the mini-market,” she said. “It’s open. We should all buy food.” It was already 4 a.m., but after dozens of calls and messages, it felt like only minutes had passed.

My brother-in-law and I decided to head down. Outside, still under the cover of night, men and women were filling plastic Minalba bottles with drinking water from communal taps. We started walking along a long path lined with palm trees and tropical vegetation. Dozens of apartments had their lights on. Through windows, you could see families gathered on sofas, trying to tune into CNN en Español or some YouTube livestream from Miami.

In front of the mini-market, a long — very long — line was already forming. We walked up to the front of the line to see how fast it was moving. They were letting people in by turns, rationing categories of products. “Charge your phones,” some people said. No one really seemed to understand what was happening. The initial fear had given way to a calmer, collective confusion.

The line dragged on for hours. Rumors kept bubbling up. “This minister is dead,” people said on Twitter. “This other one too — a very good source told me so,” others said in the line. None of it was true. They were alive.

The sky began to turn a bright pink. An hour away, in Caracas where it was calm and eerily silent after the bombs, my friends reported the sky there had also turned a bright pink — but there, a dense layer of smog hung between office towers and the massive, multicolored mountain that crowns the city. No one had slept, here or there. My phone kept buzzing.

Then, President Donald Trump posted on Truth Social. He announced that Nicolás Maduro and Cilia Flores, the country’s authoritarian leader and his wife, had been “captured and flown out of the Country.” I mentioned it to the people in the line, but many didn’t seem to believe it. “People here are shouting and cheering out loud,” a friend who lives in Chacao, a staunch opposition district in Caracas, told me. “Same here,” said another friend vacationing in Margarita, the country’s largest Caribbean island.

And then the crowd gathered in the queue — this sea of people coiling and gossiping outside the mini-market — started shouting and celebrating too. A young woman in pajamas, with teary happy eyes, walked up and down the line announcing, “Trump just said they took Maduro.” A man pulled out a bottle of prosecco and began passing it around, pouring it into small cardboard coffee cups as people toasted. A woman called her relatives abroad, part of Venezuela’s 8 million-strong diaspora, to announce they would soon meet again in Venezuela. But even in the middle of the euphoria, another question began to surface, whispered and then spoken aloud:

“Okay, but then who’s in charge now?”

By 8 a.m., the line had barely moved. With the people we’d met queuing, we started taking turns holding our spots. There wasn’t much left anyway: lots of water, cartons of eggs, endless snacks and chips.

We walked back to the apartment for a while, sipping cups of coffee we took from our friends’ house under the songs of great kiskadees and parrots darting through dense trees and every kind of palm.

It felt like the culmination of a series of strange vignettes in a mestizo country prone to superstition and mystic beliefs. Months earlier, the Catholic Church had canonized Venezuela’s first saints. “From today on, everything changes,” a priest had said during Mass. “Venezuela becomes holy land.” Then, the first Andean condor chick was born in Venezuela in more than 20 years. “The spell is broken,” people joked. That very night, before the bombing, a lunar halo unfurled across the sky. “It’s good luck,” I said at the club, beneath broad tropical leaves in the garden, after a midnight swim in the sea.

But reality was starting to come into focus. First, a statement, read by a pro-government journalist on VTV, the state channel, looped over and over. Then an audio message from Vice President Delcy Rodríguez rejecting what she called a “kidnapping” and demanding proof of life of Maduro. Then a video from Defense Minister Vladimir Padrino. Then Diosdado Cabello — the interior minister, overseer of the regime’s sinister security apparatus — surrounded by agents on the streets of Caracas, calling for calm and rejecting the intervention.

Maduro was gone, but the regime was still, more or less, intact.

Uncertainty and anxiety grew. Some people in the line even began to sense — to fear — that what might come next could be an intensification of authoritarianism: Maduro out; the harder liners fully in.

The consensus among the club’s members, for now, was that everyone should stay put. Going back up to Caracas would be madness, people said: tunnels through the hills likely closed, checkpoints everywhere, a heavily militarized city. Or at least we thought.

“They took the dumbest one,” a security guard told us, as celebration curdled into worry. “They left us with the most toxic one,” he said, referring to the interior minister.

Then I noticed — amid people riding bikes and kids running around — others frantically packing their cars. Friends of my brother-in-law, parents of his friends, appeared in their white SUV packed with bags outside of the building’s entrance. “The highway’s open again,” they said. “We’re leaving now, back to Caracas.”

My 11-year-old nephew looked at me quizzically. “Uncle, what’s happening?,” he asked. “Why is everyone leaving so fast, like they’re running away? It’s Saturday.”

We went back up to the apartment to pack. If everybody else was leaving, we were leaving too.

The coastal towns on the drive back to Caracas were empty, save for long lines of people outside supermarkets and pharmacies. We passed the port of La Guaira, where we saw warehouses blown apart, fences charred and twisted and a large cloud of smoke still rising from the site of the American strike.

As we drove up towards Caracas, soldiers — visibly tense, suspicious, scared — had blocked the highway with concrete barriers, leaving only a single lane open. And inside one of the tunnels in the hillsides before the city, one entire lane was occupied by tanks.

Caracas itself was eerily calm. Half-empty. Lines of cars snaked around gas stations. More lines at supermarkets, pharmacies, drive-throughs. It was clear everyone was trying to stock up, just in case the country plunged into chaos.

Unlike the euphoric crowds of the Venezuelan diasporathat gathered in cities like New York, Buenos Aires, Miami and Bogotá — part of the nearly eight million migrants and refugees who fled a humanitarian collapse, massive economic contraction and authoritarian rule under Maduro — there were no public celebrations in Caracas. Here, the constant, ingrained, fear of repression and reprisals by the regime prevailed. The regime might be decapitated, but it was still very much alive.

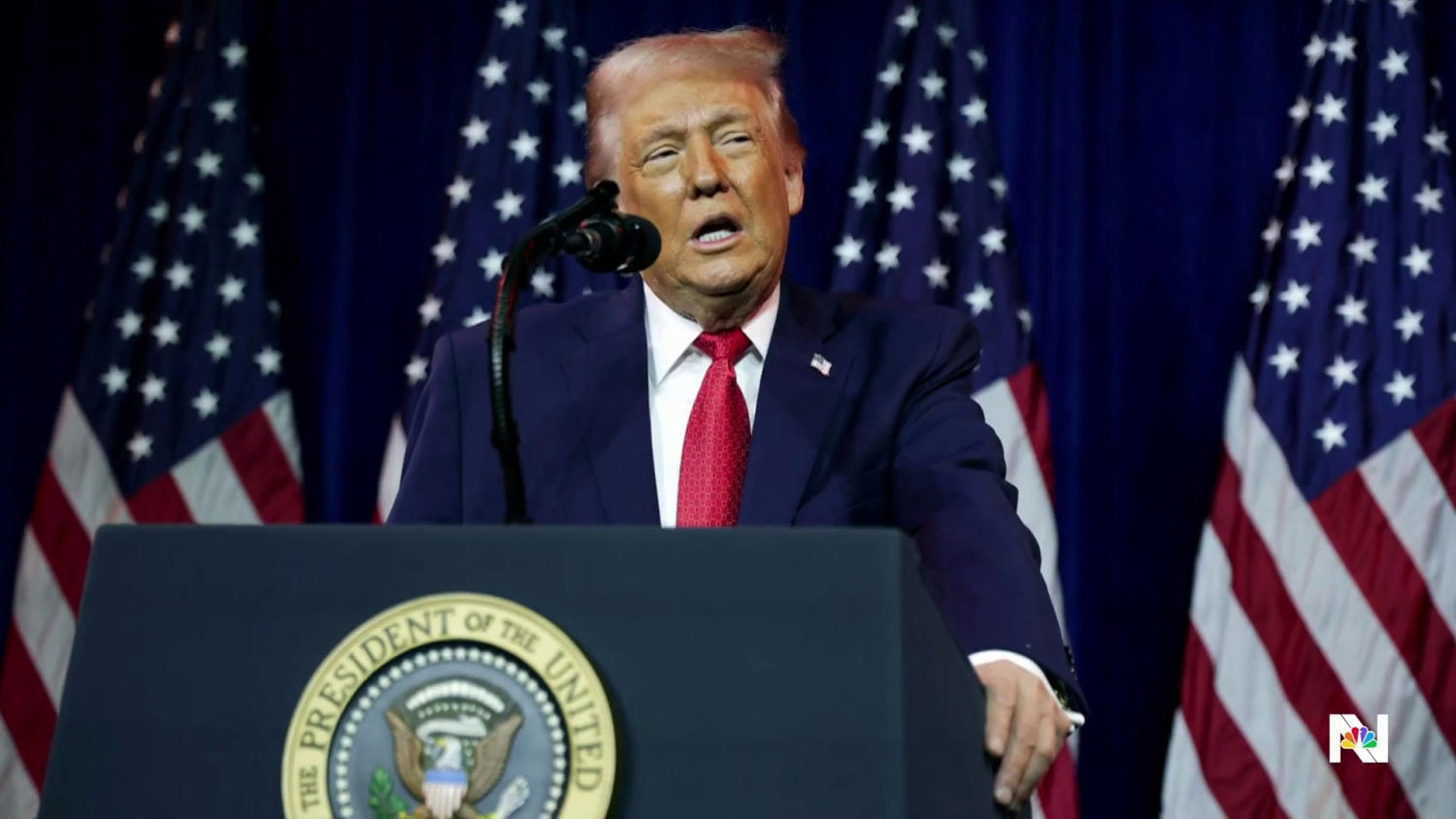

When I finally got home — I hadn’t been able to sleep at all — I turned on the TV, opened YouTube and livestreamed Trump’s press-conference. “We’re going to run the country until such time as we can do a safe, proper and judicious transition,” Trump said. And then, almost as an afterthought, he casually said the quiet part out loud: “We’re going to have our very large United States oil companies … go in, spend billions of dollars.” He also threatened the remaining rulers with a “second, bigger, wave” of bombing.

“This is madness”, a friend texted in a group chat. “We are going to have a Trump Tower in Las Mercedes,” another friend said, referring to a busy commercial district in Caracas. Memes start flowing in. An AI-generated strip mall in the middle of Caracas with Target, T.J. Max, Best Buy and Appleebee’s. My friends start joking by saying their names in English: “Raphael,” “Mary Anne,” “Gerald.”

After years of so many crises and shocks layered atop one another, Venezuelans have become what Lebanese writer Nassim Nicholas Taleb describes as antifragile: shaped and strengthened by disorder itself.

Then we’re back to seriousness. “I think it’s alarming he is saying he is keeping the oil,” a female friend said. “Whatever,” a male friend said. Other groups are buzzing by the second. Trump then lambasts María Corina Machado, the highly popular Nobel Peace Prize winner and opposition leader. The group chats explode. “Maybe he doesn’t know who she is,” a young woman said. “Maybe he is mixing Delcy with María Corina,” others suggested, trying to find meaning in the sudden reversal of sympathies from the Trump administration.

In Venezuela, it’s still not clear where we’re headed.

During the weekend, Caracas felt like a ghost town: neon billboards and blinking giant Santa Clauses flickering over empty streets. But by Monday, cars were back on the streets of Caracas. Some people returned to work; others shifted to remote mode; others clung to the last threads of the Christmas holidays like a life raft. On Sunday, Delcy Rodríguez — after defiantly rejecting Trump and Secretary of State Marco Rubio in her address following the Mar-a-Lago press conference — chaired her first cabinet meeting. She announced an “agenda of cooperation” with Washington, once the regime’s sworn enemy. The direction of the wind was suddenly clear. That same Monday, Rodríguez was officially proclaimed interim president by the National Assembly.

She stood surrounded by figures who also appear in Maduro’s indictment and who, because of the rivalries inside the Chavista hydra, could quickly become her challengers and main source of instability. On Monday night, there was a shootingnear the presidential palace — apparently accidental, a case of friendly fire involving government forces and drones — but for several hours, videos circulated of bullets ripping through the night sky, feeding fears of a violent internal rupture within the regime itself.

That day, I avoided leaving the house. Colectivos — pro-government urban militias armed with assault rifles — tightened their grip. Reports spread of their checkpointson highways and across parts of the city, allegedly searching phones for “incriminating” messages. A new state-of-emergency law declared that anyone who had “supported” the operation could be arrested. That same day, 14 journalists, almost all from international outlets, were detained, only to be released later that night.

Two days later, the always frenetic Avenida Francisco de Miranda — lined with 3D screens, LED billboards and ground-floor shops beneath 1950s-era buildings — was once again packed with people crossing the street, motorcycles weaving through traffic and cars flowing through every direction. The day before, I went out to eat.

Despite analysts in the international press warning of a potential spiral of violence like Iraq or Libya, the restaurant was, like others in the commercial areas, half-full again with people eating and drinking while talking through what might come next. With normal work hours disrupted, CrossFit boxes and yoga studios are full at random moments of the day.

On the radio, only classical music played: no journalists, no commentary, no pop music, just long stretches of symphonies. That Wednesday — a day after Trump announced he would be “turning over” millions of barrels of oil to the United States and state-owned national oil company PDVSA’s subsequent acceptance, and as Rubio’s plan began to take shape: stabilization first, economic recovery next, and only then a democratic transition — I went to see the new Avatar at the movie theater. There weren’t many people, but there were some. Between explosions and Marines on screen, we laughed at the resemblance to our new normal. The first film, released in 2009, after all, had oddly enough mentioned Marines fighting a war in Venezuela.

As I walked out of the theater, I picked up my phone to read that Trump was on Truth Social again declaring that Venezuela would now buy “ONLY American Made Products” — as if announcing the return of the consumerist Venezuela that existed before the collapse. I wondered to myself if the AI-generated meme of an even-more Americanized Caracas might actually come true.

The week has been a never-ending flux of buzzing Whatsapp chats. Friends’ chats, news chats, family chats, chats of a plethora of organizations and events I belong to or have belonged to. “I’m very nervous about this,” a young NGO worker fretted. “I’m not seeing accountability. I’m not seeing María Corina.” “It’s only been five days, wait and see,” a younger tech writer replied. “Chavismo now wants to save itself,” a woman in finance predicted, “[Government officials] will say ‘yes’ to a lot.” Others reported on the places that are open and how they are seeing the streets. “This is like a collective episode of schizophrenia,” a psychologist texted. “Twin Peaks,” her friend replied. “Is the U.S. Embassy reopening?” another asked. “I want the flights to Miami back.”

As Trump’s demands to Rodriguez became clearer, a growing sense of outrage began to take hold over many in Venezuela over the absence of any mention of the release of nearly 1,000 political prisoners — arguably the central cause around which organized Venezuelan civil society has rallied. Everybody seemed on alert, waiting for news of liberations. In the chats, most people seem confused with Trump’s rambling and more at ease with Rubio, a long-standing champion of the Venezuelan cause. “This dude being involved gives me a lot of trust,” an entrepreneur said.

Amid this emotional roller coaster, a verdict settled in the many group chats: Perhaps Trump just rambles. Perhaps Rubio will save face and push for an actual transition to democracy. Perhaps this will bring major money flowing into the country. Perhaps this is the beginning of the long walk to democracy. “I think things are getting better,” an office cleaning lady told me, “Maduro is gone.”

Or perhaps it will all stay politically the same, but with U.S companies harbingering a long-desired economic boom in an oil-dependent country with triple-digit inflation and 70 percent of the population earning less than $300 a month. A Saudi Arabia of the Caribbean: authoritarian, stable, useful and strategically friendly. “I think this is the best that could happen to the economy,” a 30-something professional told me.

Maybe the remaining figureheads will make the same calculus as the cynical Italian aristocrats struggling to hold onto power in Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s novel, The Leopard: "If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change."

Or maybe not. Maybe it’s the beginning of something else.

On Thursday, finally, the release of political prisoners was announced — apparently thanks to a push by the Trump administration, who said in exchange it would cancel the possibility of a second round of bombings. In WhatsApp groups and across social media, optimism surged at the prospect of seeing around 1,000 Venezuelans unjustly imprisoned finally set free. But after the hours-long frenzy — after alleged lists with hundreds of people, rumors, and names of well-known detainees said to be walking out — by Friday morning only nine had actually left their cells. The process is fragile; disappointment can kick in at any moment.

Still, the buzz continues in chats, conversations and social media posts alike: optimism, for now, holds.

.png)

English (US)

English (US)