Gov. Gavin Newsom has been fighting for more than a year with Republicans and members of his own party about whether his fuel standards will raise gas prices for Californians.

Turns out, they already have. But no one noticed.

The rules that went into effect July 1 requiring companies to lower the carbon content of their transportation fuels marked an occasion to renew hostilities. President Donald Trump contrasted California's prices with the rest of the country's. ("All they do is they keep adding taxes. Terrible governor, doesn't know what he's doing.")

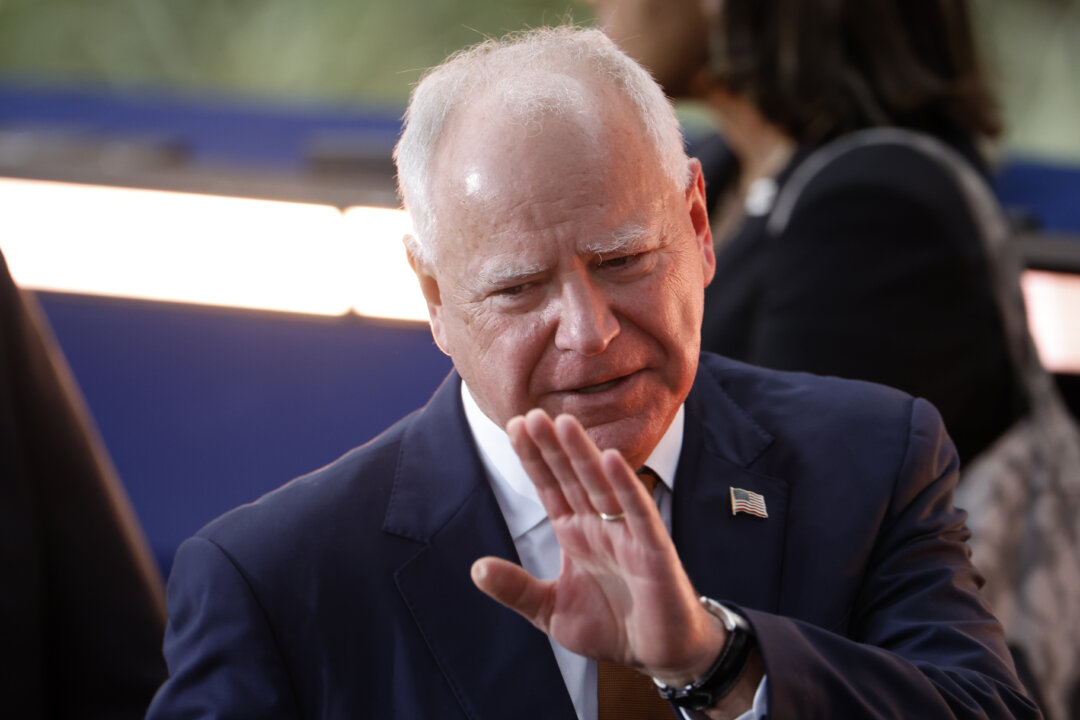

A state Republican lawmaker launched a petition to "repeal Gov. Newsom's 65-cent gas price hike," and a gubernatorial candidate held a press conference at a gas station to propose repealing the rules. Even Democrats couldn't resist introducing a bill to freeze prices under the program, which sets a steadily tightening emissions limit and lets producers buy and sell credits to meet it.

After the augured price hike failed to materialize, Newsom took a victory lap. "Did gas prices go up by 65 cents at the pump?" his office asked in a press release July 2. "No."

But according to two industry sources granted anonymity to discuss proprietary market data, refiners started incorporating the new rules into their prices in January. As a result, California's gas prices have been roughly 5-8 cents per gallon higher at the pump since then, despite the underlying regulations not taking effect until this month. And drivers are out roughly $300 million that they shouldn't have been charged, according to their calculations.

State officials confirmed the error to me on Wednesday, the same day they sent a memo to board members detailing the findings — and said it shows the program is ultimately working as intended, price-wise.

"It does sort of validate the points that we were making over time," said California Air Resources Board Chair Liane Randolph. "The pricing has played out in pretty much the way we anticipated."

The episode illustrates the degree to which rhetoric and reality are almost entirely divorced in California's interminable gas-price wars — and the difficulty of puncturing the curtain that separates the two.

"It was priced in on Jan. 1, and no one really knew about it," said Will Faulkner, a carbon market analyst.

California gas prices have long been a topic of fascination and speculation, thanks to perpetually high costs that exceed even the levels predicted by the low-carbon fuel standard, the state's 61-cent gas tax, and another trading program that covers all industrial emissions. (A state analysis in 2019 pinned some of the responsibility on drivers, who "continue to purchase higher-priced brands despite having many options.")

And while California's climate policies are a perennial culprit, the low-carbon rule has been a particular lightning rod. Part of the reason is that it's been twisting in the wind: The California Air Resources Board (CARB) began updating it in mid-2023 and didn't finish until the end of 2024 — a long time even by California standards — as environmental groups and industry fought over how stringent it would be and which fuels it would incentivize.

That left a lot of time for politics — like a bill by state Republicans to freeze the program, a publicity campaign by Chevron at its gas stations and a proposal by Newsom to boost in-state gasoline's ethanol content — and a lot of time for policy analysis.

After CARB produced — and then walked back — an estimate that the changes could raise gas prices by 47 cents per gallon, climate economist Danny Cullenward released an analysis that found worst-case estimates of 65 cents per gallon in the near term, 85 cents by 2030 and nearly $1.50 per gallon by 2035. Another academic, University of Southern California professor Michael Mische, produced an estimate of $8.43 per gallon by 2026 based on refinery closures plus the rules. (Newsom's office responded last month: "Why not $10 by 2026? $12? Just because one crackpot "expert" says something does not make it true.")

At the same time, Newsom, already acutely sensitive to gas prices after they spiked to $6.44 per gallon in 2022, was picking a separate fight with oil companies over price spikes related to refinery outages. That culminated in a pair of laws giving the state more power to investigate price gouging and oversee refineries' maintenance schedules — and pulled neighboring governors into the fray over concerns that they could raise prices in their own states.

Given all the scrutiny, it's fairly stunning that no one pointed out that the program was already priced in at the pump starting in January. That's not even accounting for the fact that since it wasn't in effect, refiners kept the extra money that they would have spent on buying credits. At an average of 7 cents per gallon over 4.3 billion gallons of gas sold, they collected roughly $300 million before the rules actually kicked in.

"No one's paying attention," Faulkner said. "The No. 1 thing in Sacramento is affordability, and $300 million just went poof."

The actual process that led to the snafu was largely due to an administrative hiccup. After CARB approved the amendments in November, they submitted them to the Office of Administrative Law, a final step before they took effect. But OAL rejected them over technical issues, so CARB had to resubmit them — and it wasn't clear whether they would take effect retroactively, on Jan. 1, or whenever the agency approved them.

Enter OPIS, an oil price reporting service owned by Dow Jones that performs the function of converting the carbon price into the cents-per-gallon price for fuel trading purposes. OPIS started incorporating the new numbers in January, on the assumption that the amendments would take effect retroactively. It didn't remove the added cost until late May, once regulators said the rules would take effect in July, so for five months OPIS' price incorrectly reflected the tighter rules.

"OPIS started 2025 using the proposed targets based on communications from CARB that the agency planned to implement the targets retroactively to Jan. 1," spokesperson Lauren McCabe said in an email. "Once CARB indicated on May 16 that it was targeting a July 1 implementation, we updated the LCFS pricing methodology to reflect the outgoing targets, effective May 27. After the amendments were finalized on June 27, we updated our LCFS pricing methodology to reflect those targets, effective July 1."

Randolph said CARB had alerted Newsom and other officials in the spring, when the premature pass-through became apparent. "When we saw what was happening in the data, we certainly let the governor's staff know, and we certainly let DPMO know," she said. When asked for comment, Newsom's office referred me to CARB.

State officials say they're looking into it. "The Division of Petroleum Market Oversight (DPMO) is aware of this issue and, in collaboration with other state agencies, is engaging with market participants to resolve this fairly for California consumers," California Energy Commission spokesperson Niki Woodard said in an email.

Bigger picture, this is good news for California at a fairly dark time for U.S. climate policy (although environmentalists are decidedly split on the program's climate bona fides). The low-carbon fuel standard is one of the only remaining major planks of California's climate policies that Trump hasn't touched. He signed a law last month removing California's ability to enforce its electric vehicle sales targets. Renewable energy targets are going to get harder to meet with the One Big Beautiful Bill Act's rollback of federal tax incentives. And carbon prices fell after Trump asked the Justice Department to specifically block the state's carbon-trading program, among other laws.

When it comes to the politicians who have been sparring for months over climate priorities and cost of living for Californians, this debacle leaves both sides looking hollow.

"It was a rhetorically useful bit of data for people to support the messages they wanted to put out anyway,” said Colin Murphy, deputy director of University of California, Davis' Policy Institute for Energy, Environment and the Economy. “And that's politics."

.png)

English (US)

English (US)