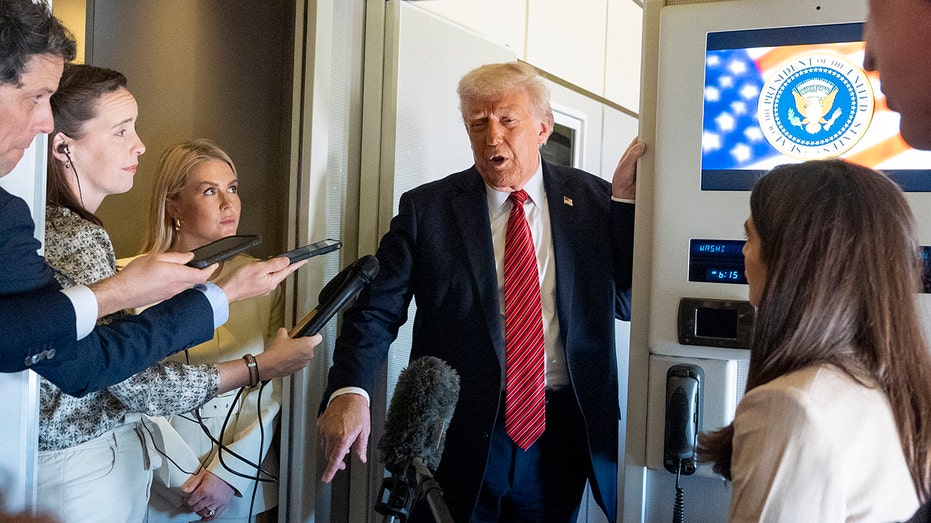

President Trump’s executive order on Monday turned a harsh spotlight on pharmaceutical companies’ long-standing practice of charging Americans far more for prescription drugs than they charge consumers in other countries.

The order’s language remains vague — it mentions only future “price targets” and possible enforcement mechanisms — but the message is unmistakable: The U.S. government will no longer tolerate paying inflated prices for drugs when European governments negotiate far lower ones.

Americans crushed by high drug costs also vote — and they can elect a president and Congress willing to rewrite the rules.

Trump’s order addresses just one part of a larger, deeply rooted problem: the runaway cost of prescription drugs in the United States. A major contributor to that cost is the pricing of patent-protected drugs, which face no competition and often come with astronomical price tags.

Pharmaceutical companies now operate under a politically dangerous business model. They enjoy government-granted patent protections to block competition, while squeezing insurers and patients to extract maximum profit. This isn’t capitalism. It’s a merger of legal monopoly and short-sighted corporate greed — a textbook example of protectionism paired with profit-maximization stripped of ethical restraint.

Legally, these companies act within their rights. But politically, they’re playing with fire. Americans crushed by high drug costs also vote — and they can elect a president and Congress willing to rewrite the rules. Trump’s executive order sends a warning. If the pressure builds, Congress will follow with legislation.

In a free-market ideal, companies compete to win consumers by offering better, cheaper products. That’s good. But when a company invents something new — especially something as vital as a life-saving drug — it deserves a temporary monopoly to recoup research and development costs. That’s why the government issues patents. This, too, is good.

Yet, once the government grants monopoly rights, we’re no longer in a purely free market. The question then becomes: What responsibility does the government have not just to the patent-holder but also to the consumers who depend on that drug for survival?

Stephen Moore, a senior fellow at the Heritage Foundation, recently addressed one side of the debate in the Washington Times. He criticized so-called “compounders” — companies that tweak existing drugs and resell them without going through the same research-and-development and FDA approval process. Moore called these copycats unsafe and accused them of free-riding on innovation.

Compounders clearly respond to market demand but so do pharmaceutical companies charging monopoly prices under government protection. Both “cash in.” One simply does so with fewer legal barriers.

If the government takes seriously its role in enforcing patents, it must also consider whether those monopolies serve the public good — or exploit it. Monopoly pricing for essential drugs carries moral consequences. Government can’t ignore them.

This brings us to another, equally troubling aspect of the problem: the "America last" approach embedded in current drug pricing practices.

Many Americans struggle to afford life-changing medications, while pharmaceutical companies sell those same drugs overseas — at a fraction of the U.S. price. Industry defenders argue that American consumers must bear the brunt of R and D costs, allowing foreign countries to buy at lower “incremental” prices. Without those sales, they say, U.S. prices would rise even higher.

But that argument wears thin.

Charles Rotter recently posted on X that U.S. drug pricing amounts to backdoor foreign aid. “Other countries’ healthcare systems stay sustainable and affordable because American patients bankroll the difference,” he wrote. “Why should a senior in the U.S. pay dramatically more for the same pill than a senior in France, effectively subsidizing France’s national health system?”

Pharmaceutical pricing isn’t just a pocketbook problem. It reflects a broader failure to prioritize American citizens. Companies obeying the letter of the law still fail the test of loyalty and common sense. The system persists only because voters haven’t yet forced change. Trump’s executive order signals they’re starting to.

Congress could go further by revisiting patent protections and demanding greater price transparency. The message to Big Pharma should be clear: You can choose to act like responsible corporate citizens and stop bleeding patients dry, or you can wait for the government to do it for you.

If drug companies continue to exploit their monopolies, they shouldn’t be surprised when voters — and their elected representatives — decide to break them.

.png)

3 hours ago

3

3 hours ago

3

English (US)

English (US)